One of the most discussed topics regarding the dating of the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages is the fall of the Western Roman Empire. Western Roman indeed, the great Roman Empire was divided, with the Eastern Roman Empire not ceasing to exist until its decline at the end of the Middle Ages, which is again seen as an endpoint of the Middle Ages and transition to the Renaissance. However, one event is rarely solely responsible for the end of an era. Often it involves a series of events that over a longer period lead to a shift in the existing order.

Thus, one could not only designate the year 476 AD (Fall of the Western Roman Empire where the last emperor, Romulus Augustulus, is deposed by Odoacer, leader of Germanic mercenaries within the Roman army) as the end of antiquity and the beginning of the Middle Ages. One could just as well mention other events, such as the sackings of Rome in 410 AD and 455 AD by respectively the Visigoths and the Vandals, Germanic tribes displaced by the arrival of the Huns in Europe. The fourth century marked a Roman Empire that was forced to incorporate Germans as foederati, residents without citizenship, but forced to provide (military) assistance in exchange for protection and inclusion within the empire’s borders. This further led to decline. The difficulty of letting one event be responsible for the end and beginning of a period quickly becomes clear. This also keeps the discussion alive within historiography about where to end antiquity and begin the Middle Ages. It depends on what you look at. Tradition, however, maintains 476 AD as the transition, one must give it a year somehow, which is convenient for people. However, identifying the fall of the Western Roman Empire is anything but an easy matter, as it involves various aspects that ultimately lead to its end.

Christianity

After the death of Jesus, his apostles set out to preach Jesus’ teachings. One of the apostles who was most fanatic in this was Paul, about whom I have written earlier. Paul also went to Rome to bring Christianity there and eventually achieved martyrdom. Christianity was and is fundamentally a pacifist religion, whereas the Romans had a war god, Mars. Additionally, the Christian faith was primarily a monotheistic religion. And that was a problem in the Roman Empire, as the Roman state religion adhered to many gods. The Romans can be said to be reasonably tolerant of other religions and ideologies, unless one completely abstained from the Roman cult, which was polytheistic in nature. Christians were therefore, as the Jews had previously experienced until they were recognized by the Roman emperor(s) in the first century, seen as a danger to the unity of the state. They would be bad for trade because they drove merchants away from temples where they could. The Romans also watched the rituals of the Christians with suspicion, they were seen as cannibals because they ate the flesh and blood of Christ. As a result, they were regularly subjected to persecutions. Examples of this can be found in all three centuries; in the first century, for example, by Nero, who used Christians as torches along the road, in the second under Marcus Aurelius (177), and in the third and fourth respectively under Decius (250), Valerian (257), and Diocletian (303). The persecutions only stopped with the Edict of Milan in 313, which officially allowed the religion within the empire and granted citizens the right to freedom of religion. This allowed the following among Christians to grow strongly. More and more people within the empire became followers of the Christian faith, including soldiers. However, they came into conflict with their faith and their profession, as these two were difficult to reconcile. Historians often point out that with the advent of Christianity, the military strength was gradually undermined.

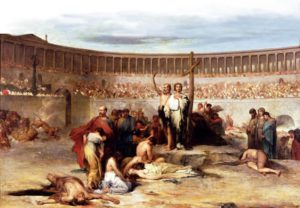

Christians are slaughtered for entertainment in front of a frenzied audience. Source: Historia.nl

Declining Power

The Roman Empire reached its peak at the beginning of the third century (202 AD) under Emperor Septimius Severus, who annexed a vast territory in Mesopotamia to the already considerable empire. It is often thought that the greatest extent was reached under Trajan, but this is not true because he could not definitively establish his authority in the same area, although he made successful incursions there, as J. Lendering indicates in a book review on his weblog Mainzer Beobachter about Maarten van Rossem’s book “The End of the Roman Empire”. But here too: the larger an empire, the harder it is to manage. A larger empire has more border kilometers and needs more soldiers and thus more pay. That means higher taxes. Due to the call for a larger army, Roman citizens could no longer be exclusively recruited for military service. Increasingly, these were foederati or prisoners of war. Furthermore, a large part of the third century was characterized by internal chaos and civil wars within the empire. The period is known in history as the crisis of the third century and the rule of competing soldier emperors. Soldiers often appointed their commander in the hope that more pay would follow. Due to internal strife, much less loot came in than before. To make matters worse, the pressure from various tribes on the outer borders became increasingly greater. In the Parthians, the Romans found an opponent to reckon with on their eastern borders. They suffered several major defeats against the Parthians (territory largely modern-day Iran) between the mid-first century BC and the early third century AD and later at the hands of the successors of the Parthians; the Sassanid Empire. In the west, barbarian invasions became more frequent and intense. The Germans increasingly banded together in organized (tribal) alliances in the fight against the Romans. They had often fought in the ranks of the Romans and now used their acquired military knowledge against their old employer. The emperor sought refuge in strengthening the army to better face the many enemies, but more troops meant more expenses. The silver content in a coin was drastically reduced to keep everything funded. As a result of currency devaluations and people leaving both cities and border areas, the economy in the west collapsed. Only with the arrival of Emperor Diocletian did some peace return to the empire.

Roman Empire around 117 A.D.

A divided Empire

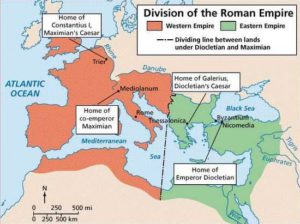

Both Diocletian and Constantine implemented various reforms in their attempts to further restore the empire. Both in administrative areas (expansion of the bureaucracy), economic areas (prices for goods were controlled), and the actual division of power (Tetrarchy). As a result, Rome was no longer the seat of power. In 285 AD, the Roman Empire was administratively split in two. From then on, there would be a western part and an eastern part. This division is called the tetrarchy, in which Diocletian, emperor at the time, appointed a co-emperor and two sub-emperors. It was hoped that by dividing the empire, attacks from different sides could be better parried. Ultimately, the emperors quarreled over succession, from which Constantine the Great emerged victorious after having a vision of the Christian cross on the eve of a decisive battle against his greatest enemy, which would bring him victory. Constantine indeed won and became the first Christian emperor of the empire. Constantine moved his seat of government to the richer Constantinople (later Byzantium). After the death of Theodosius the Great (395), who had to admit the Visigoths under Alaric I within the borders of the empire, a definitive division between East and West followed. Armies of both empires no longer supported each other in military campaigns, leading to further weakening the military.

The Tetrarchy around 230 n.Chr. Source: Historiek.net

Taxes

Due to the many (civil) wars within the empire, residents were burdened with increasingly higher taxes. These could no longer be borne by the backbone of the economy, the free tenant farmers (coloni). Many farmers were forced to leave their lands in the hope of a better existence. This led to less agricultural production; large tracts of farmland were left uncultivated. Markets became smaller. Attempts were made to reverse the tide by making the profession hereditary and tied to the land, so that the large exodus from the countryside would be stopped. The abandoned pieces of land were often seized by large landowners who employed slaves there. The large landowners eventually became lords of both coloni (free tenant farmers) and slaves. Serfdom (bondage) thus arose. However, due to less territory being conquered, there were also fewer slaves available. This resulted in smaller pieces of land being exploited and large landowners becoming increasingly independent of Rome. The government could no longer manage the countryside. The villas in the countryside became administrative centers in a certain area.

Migrations and Plague

During these economic and social developments, the Roman Empire also had to deal with the outbreak of plague epidemics. This further weakened the economy. Cities shrank significantly and trade became more small-scale. The first major epidemic occurred under Marcus Aurelius (r. 161-180). It is doubted whether this was real plague, but in any case, an estimated ten percent of the empire’s inhabitants died. Especially among the soldiers, the number of victims was high. Eventually, the army could not withstand Germanic invasions, forcing the emperor to lead the army himself (successfully). However, the threat of Germanic invasions remained, and increasingly the Romans were forced to incorporate Germans in large numbers into the empire. These foederati subjected themselves to Roman laws. In exchange for protection within the empire, the foederati provided auxiliary troops for the legions, which increasingly consisted of Germans.

At the end of the fourth century, however, the Huns (an Asian equestrian people from the Mongolian regions) were displaced. They drove various Germanic peoples into flight, such as the Visigoths, for example. Rome was sacked in 410 AD by these Visigoths, who became foederati after fleeing from the Huns, and again in 455 AD by the Vandals. The event caused a tremendous shock in the old world order, Rome saw foreign troops in the city for the first time since the fourth century BC. The Huns flooded European territory and even took Milan and Ravenna and also threatened Rome. The last great victory of the Romans took place on the Catalaunian Fields where the Roman general Aetius defeated the Huns under Attila. The last Roman emperor, Romulus Augustulus, was eventually deposed in 476 by Odoacer, who thus became the first barbarian king of Italy.

Complex

As we can deduce from the above, the fall of the Western Roman Empire is thus a complex set of factors over a longer period that lead to the end of a period of Roman rule in the west. Disease, famine, the size of the empire, migrations, the advent of Christianity and thus pacifism in the empire, the incorporation of Germans into the army and their growing importance in that army, even in high positions, the division of the empire, military defeats, good emperors, bad emperors, sky-high taxes that can no longer be borne, the lack of loot due to the absence of victories, de-urbanization, civil war, legislation, so many causes play a role in the disintegration of the empire, that when choosing a year to periodize the final fall, the year 475 AD was chosen to somewhat periodize it, and one looks mainly at a break with the past on an institutional level. However, the Latin culture further merged with the Germanic, a process that would take centuries and to this day you find elements of both around you.

Leave a Reply